Medical Devices

A certificate of compliance with ISO-13485 (Medical Devices – Quality Management Systems – Requirements... View more

What Are In Vitro Diagnostic Tests, and How Are They Regulated?

-

What Are In Vitro Diagnostic Tests, and How Are They Regulated?

What is in vitro diagnostic use?

In vitro diagnostics are tests done on samples such as blood or tissue that have been taken from the human body. In vitro diagnostics can detect diseases or other conditions, and can be used to monitor a person’s overall health to help cure, treat, or prevent diseases.

Overview

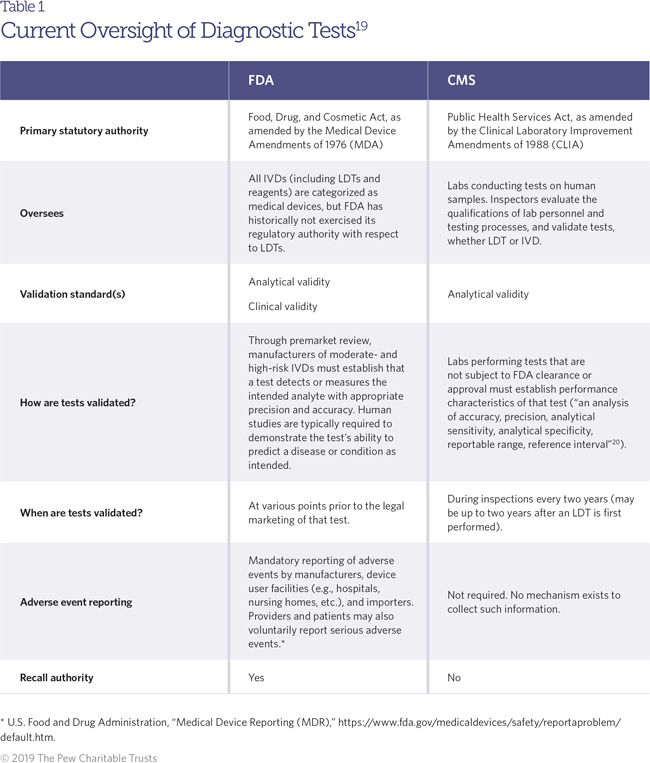

Health care providers rely on a variety of tools to diagnose conditions and guide treatment decisions. Among the most common and widely used are in vitro diagnostics (IVDs), which are clinical tests that analyze samples taken from the human body. Patients may receive—or forgo—medical care based on diagnostic test results, making it critically important that tests are reliable. These tests are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration as medical devices, which means manufacturers must submit studies confirming a test’s accuracy and usefulness in diagnosing a particular condition before bringing it to market. However, FDA has historically exempted from this requirement any IVDs that are developed and used within the same laboratory, often referred to as laboratory-developed tests (LDTs). Though some test developers dispute that FDA has jurisdiction over LDTs—arguing that the tests are more properly seen as procedures that constitute the practice of medicine—the agency maintains that these tests are devices and fall under agency jurisdiction through the Medical Device Amendments of 1976. At the time of that bill’s passage, LDTs were used mostly for rare diseases and generally relied on manual (rather than automated or software-based) analysis and interpretation. Because they posed a lower risk, LDTs were exempted from the more stringent regulatory requirements that apply to other IVDs. However, LDTs have become increasingly complex in recent years, driven by advances in technology that have made elaborate analyses like genetic sequencing both quicker and more affordable. Much like FDA-reviewed IVDs, LDTs are essential to the diagnosis and treatment of many conditions and are an indispensable tool in the practice of precision medicine—a still-emerging but highly promising approach to clinical care that relies heavily on genetic or molecular profiling of patients. But while LDTs have evolved, the FDA continues to exercise relatively little oversight over them.

What are commercial IVDs and how are they regulated?

IVDs1 are used to analyze human samples such as blood and saliva, either by measuring the concentration of specific substances, or analytes (such as sodium and cholesterol), or by detecting the presence or absence of a particular marker or set of markers, such as a genetic mutation or an immune response to infection.2 Clinicians regularly use IVDs to diagnose conditions, guide treatment decisions, and even mitigate or prevent future disease (for example, through screening tests that indicate a patient’s risk of developing a given condition in the future). Since the passage of the Medical Device Amendments of 1976, FDA has regulated medical devices, which include products “intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions.3 Accordingly, FDA asserts this authority over diagnostic tests and their components (such as reagents, which are used to facilitate a chemical reaction that helps detect or measure another substance). Under the current regulatory regime, IVDs that are developed for the commercial market are subject to FDA regulatory requirements intended to ensure their safety and effectiveness. IVD regulation is risk-based, with tests falling into one of three regulatory categories. Tests are classified in the lowest tier, Class I, if they pose relatively little risk to patients and the public health if they are inaccurate (such as a cholesterol test). Moderate-risk tests, such as pregnancy tests, are categorized as Class II, while tests in the highest risk tier, Class III, are considered to pose the greatest potential risk if they are inaccurate (such as a genetic test used to select cancer therapies). These categories correspond with increasing levels of regulatory scrutiny, with most tests in Class I—and some in Class II—being exempt from premarket requirements, while most Class II and all Class III tests require some form of premarket review before they can be used with patients. FDA maintains two primary premarket review pathways for tests. The premarket approval (PMA) pathway is the more stringent of the two, requiring demonstration of safety and effectiveness before the test may be marketed. These are typically Class III tests that pose a high degree of risk, or tests that have no known equivalent on the market. The other pathway, known as the premarket notification or the “510(k)” pathway (for the section of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that describes it), does not impose the same strict evidence requirements as the PMA. It is intended for tests that can be described as “substantially equivalent” to a product already on the market, but other tests may also qualify if they are low-to-moderate risk and the manufacturer petitions the agency to reclassify it.4To be approved or cleared through either pathway, IVDs must demonstrate safety and effectiveness through analytical and clinical validation, which are key standards in determining a test’s accuracy. Analytical validation is focused on ensuring a test is able to correctly and reliably measure a particular analyte, while clinical validation is the process for determining whether the test can accurately identify a particular clinical condition in a given patient.

What are LDTs and how are they regulated?

The key distinction between FDA-reviewed IVDs and LDTs is where they are made: LDTs are designed and used in a single laboratory, and are sometimes referred to as “in-house” tests.5 LDTs are developed in facilities ranging from physicians’ offices, hospitals, and academic medical centers to large testing companies.6 Though LDTs may contain the same or similar components as FDA-reviewed tests, they must be developed and used within the same facility. FDA has historically viewed LDTs as posing a lower risk to patients than most commercial testing kits, and has exempted them from nearly all regulatory requirements under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. As such, the agency does not review these tests to ensure that they are accurate and reliable, and their exact number is unknown. Reporting to FDA is voluntary; there is no single registry of all laboratories that utilize LDTs, so estimates vary widely. While FDA has estimated that 650 laboratories develop these tests,7 the American Clinical Laboratory Association has said that the majority of the 11,633 laboratories permitted to develop and perform LDTs do so.8 In the past, most LDTs were relatively simple screens for single analytes, or tests developed to diagnose rare diseases where the lack of demand had created barriers to commercial IVD development. These tests were developed at a small scale, made with components legally marketed for clinical use, and were typically interpreted by health care professionals working directly with patients.9 In recent years, LDTs have been developed for a wider range of conditions, including infectious diseases (such as human papillomavirus, Lyme disease, and whooping cough) and cancers.10 Increasingly, these tests are marketed nationwide, sometimes by large laboratories or companies, and potentially affect many more people than the local populations who may have used them in the past. LDTs may be made with instruments and components not legally marketed for clinical use, or rely on complex algorithms and software to generate results and clinical interpretations.11 However, because these tests are developed and used within a single entity, they are still considered to be LDTs, despite in many cases being substantially similar to the commercial IVDs that are approved or cleared by FDA and then sold as prepackaged kits. Though FDA generally waives regulatory requirements for LDTs, the agency has intervened in several cases to ensure patient safety. It is important to note that an LDT is not necessarily less accurate or reliable than its FDA-reviewed counterpart. Some may perform as well as or even better than tests that have gone through the clearance or approval process, particularly if they are performed in more sophisticated laboratories with highly trained staff, or if they are relatively straightforward to administer and interpret.12 However, this is not always the case, and once an LDT is on the market it may take a substantial amount of time before problems are identified and corrected.13 In the meantime, patients receiving the test may undergo improper treatment, or forgo treatment altogether, on the basis of inaccurate results.

The role of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Oversight of these LDTs is principally conducted through a lab certification process overseen by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).14 All laboratories performing testing on human specimens are subject to regulation under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA),15 which governs the accreditation, inspection, and certification of all clinical laboratories. For those laboratories administering tests that have not received FDA clearance or approval (such as LDTs), CLIA establishes an additional set of quality standards, with a focus on affirming tests’ analytical validity—that is, whether the tests run by the lab detect or measure what they intend to.16 Analytical validations are conducted as a part of CMS laboratory surveys that occur every two years.17 However, the standards for analytical validity under the CLIA process are not the same as those applied during FDA premarket review. CLIA auditors validate tests performed by the lab to ensure that they precisely, accurately, and reliably measure relevant analytes in a given sample. But their assessment is limited to the conditions and patient population of that particular lab so—unlike FDA’s review of IVDs—a determination of analytical validity from a CLIA audit cannot be extrapolated to other sites or patient populations.18 CLIA is also not intended to assess the clinical validity of the tests performed in that lab—this type of validation is left to the labs themselves. In addition to providing oversight of labs under CLIA, CMS may also conduct a separate evaluation of particular tests in order to determine whether it will reimburse providers for their use. In making these determinations, CMS principally focuses on assessing a test’s clinical utility—that is, whether the use of the test improves patient outcomes (a standard that the FDA does not apply to its decision-making)—rather than its analytical or clinical validity.

Is oversight adequate?

In recent years, diagnostics manufacturers, patient organizations, FDA, and members of Congress in both major political parties have urged modernization of federal oversight of LDTs.21 Calls for reform are likely to increase with continued advances in diagnostic technology, the resulting changes in these tests’ clinical use, and their potential to affect thousands of patients. In response to proposals seeking to increase FDA’s oversight of the industry, groups representing the laboratory and clinical pathology fields have developed counterproposals focused on reforming oversight of laboratory processes under CLIA. These groups have historically maintained that any direct federal regulation of LDTs constitutes unwarranted regulation of the practice of medicine.22 The American Clinical Laboratory Association has also previously petitioned FDA, claiming that LDTs are not medical devices, but instead are services performed by clinical labs—a form of “medical practice” that FDA has no authority to regulate.23 Those opposed to a greater FDA role also argue that CMS provides adequate oversight, or that targeted updates to CLIA regulations would provide the reforms necessary to accommodate changes in the industry and the use of such tests. Furthermore, they maintain that any additional federal regulation of LDTs would impose an unnecessary burden on test developers, potentially hampering innovation. Proponents of greater FDA oversight, including the agency itself,24 have argued that diagnostics should be regulated based on risk, not on where tests are made, and that applying the same requirements to LDTs as apply to other IVDs would help protect patients from harm and create a more level playing field for test developers.25 Proponents of an updated regulatory system note that the diagnostics market has changed in several important ways in recent decades:

- Tests are no longer hyperlocal or just for rare diseases. LDTs are being developed by large, commercial organizations and performed for patients across state lines. These tests have also been developed for a wide range of conditions, and are increasingly being used in precision medicine to diagnose or guide treatment for serious conditions. Faulty or misleading results could now affect a broad range of patients, magnifying the potential for harm.

- Test results may be inaccurate. All diagnostic tests carry the risk of providing inaccurate results. However, the CLIA regulatory framework does not require a laboratory to demonstrate an LDT’s ability to accurately diagnose or predict the risk of a particular outcome (its clinical validity) before those tests are used on patients.26 Without this safeguard, the chance that an inaccurate test will be introduced into the market increases, potentially exposing patients to harm. These harms include:

- False-positive results, which could lead patients to pursue unnecessary treatments and also delay the timely diagnosis of underlying conditions.

- False-negative results, which can delay or prevent patients from receiving proper treatment, potentially leaving the disease or condition to progress.27

- Tests are not subject to premarket review. Neither FDA nor CMS reviews the validity of LDTs before they are on the market,28 nor does any regulator review their labeling or marketing claims to ensure they are supported by sufficient data. This means inaccurate or unreliable tests may be used for years until discovered through CLIA audits or other evaluations performed internally or by other researchers.

- Adverse events are not reported to regulators. LDT developers are not compelled to notify FDA of the tests they use, and there is no mechanism for adverse event reporting for LDTs.29This makes it challenging for FDA to identify emerging risks to the public health and respond appropriately.

- Enforcement discretion distorts the diagnostics market. Basing a test’s regulation on where it is produced creates an uneven playing field between LDT developers and other IVD developers. The cost of navigating FDA’s approval process limits developers’ incentive to conduct the research that could make a test more accurate and clinically meaningful, and instead provides an incentive to simply market tests as LDTs.

- Lack of transparency. Without oversight of product labeling, providers may lack the information necessary to adequately interpret a test’s results. Providers may also lack knowledge of the test’s performance, the basis for manufacturer claims, or even whether the test has been approved or cleared by FDA.

- Given the increasing risks associated with widespread use of lab-developed tests, and their importance in modern medical care, regulatory oversight should correspond to a test’s risk and complexity.

Conclusion

Providers and patients rely on clinical tests to inform their treatment decisions. But while technology has advanced and the way providers use diagnostic tests has evolved, the oversight framework has remained largely unchanged. IVDs and LDTs often serve the same role in clinical practice, but are subject to far different levels of oversight. This creates distortions in the diagnostics market, prevents regulators from having a comprehensive understanding of the tests used in clinical practice, and puts patients at increased risk of making consequential and perhaps irreversible medical decisions on the basis of inaccurate test results.

Sorry, there were no replies found.